WRITING

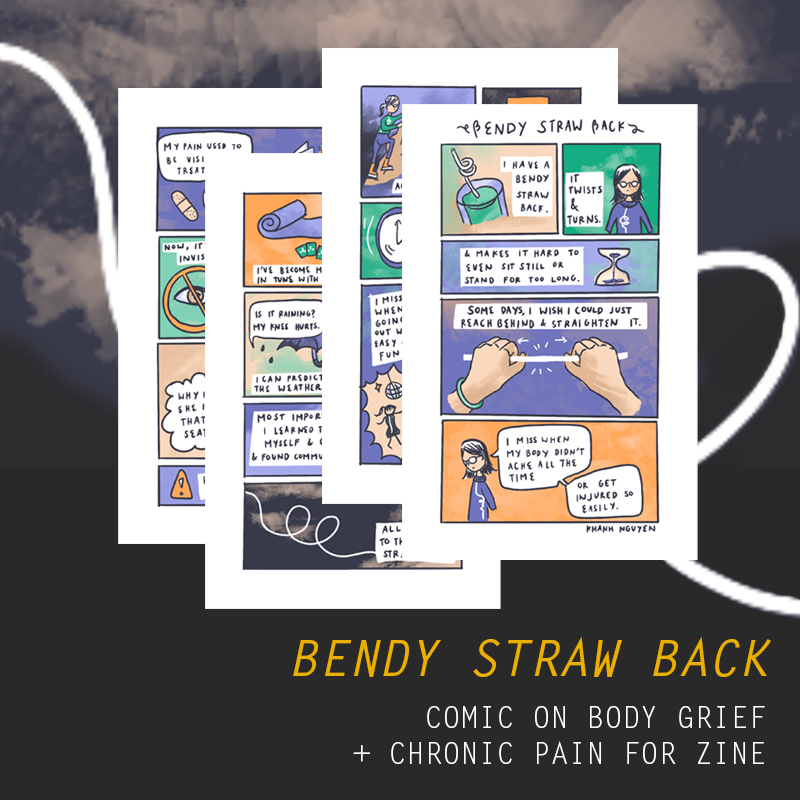

Through narrative, creative nonfiction, I explore belonging and wandering in the Southeast Asian American, chronic pain, and Queer communities.

My work has been published in Fruitslice, Hot Pot Magazine, and in the anthology Teacakes and Tarot.