duo et machina

melding metal + fabric to create sharp, sustainable garments

methods: metal fabrication, welding, sewing, collaboration, machine shop tools, dye

topics: fashion, sustainability, experiments, partner project

outputs: two looks for the MIT trashion show, resulting in a second place win

topics: fashion, sustainability, experiments, partner project

outputs: two looks for the MIT trashion show, resulting in a second place win

the brief + concept |

An obsession with machines in the world of fashion and wearables has been a common theme. The Met Gala's 2016 Manus x Machina exhibition theme comes to mind, though the intertwining of the two can be traced back to Leonardo da Vinci's inventions, and beyond. Humans and machines, now more than ever before, are intrinsically linked. As an engineer with a keen interest in empathetic fashion, it is of vital interest me to explore the ways that they loop together. Enter: Duo Et Machina, two and the machine.

Duo Et Machina is a partner project with Ryan Gulland for the 2017 MIT Trashion Show, a show aimed at promoting sustainable fashion. We wanted to introduce a mechanical engineering aspect to the world of fashion and thus designed our pieces solely with machine shop scraps. The two outfits are made of a combination of sheet metal scraps from various machine shops on campus and 3D knitter scraps donated to us from The Ministry of Supply on Newbury Street. The pieces won second-place overall for the fashion show, out of 26 entries, and the prize for Most Unexpected Materials. |

material collection |

How did we hit upon the idea? Ryan and I are both mechanical engineers with a fondness for machine shops. I was always fascinated with fashion and had designed for the Trashion Show the year prior. Ryan had recently learned how to weld. I saw the opportunity for a collaboration that put the pedal to the metal, and struck.

The first step was to decide what materials we would want to make our pieces out of. We knew we wanted to use scrap metal from the various machine shops around campus, but that was only part of the solution. Metal would be the sharp accent, but what would we make the comfortable garments out of? At the same time that we were ideating on the project, I happened to get an invitation to a Boston HUB Week talk at the Ministry of Supply, since I had painted a piece for the MIT HUB Week container. I had always been inspired by the Ministry of Supply's cutting edge approach to fashion, and invited Ryan to see if we could get some inspiration. The talk touched upon the 3D-knitter that the shop had on installation at their Newbury Street location, which they using to create custom-knit sweaters that would try to minimize the amount of waste compared to hand-knitting. While their approach did minimize waste, there were still excess scraps of wool that were discarded. Another lightning strike of an idea! Ryan and I exchanged a glance, and after the talk I told the CEO of the Ministry of Supply about our idea for Trashion and offered to take the excess wool off the shop's hands. And so our second material was found. |

sketching and ideation |

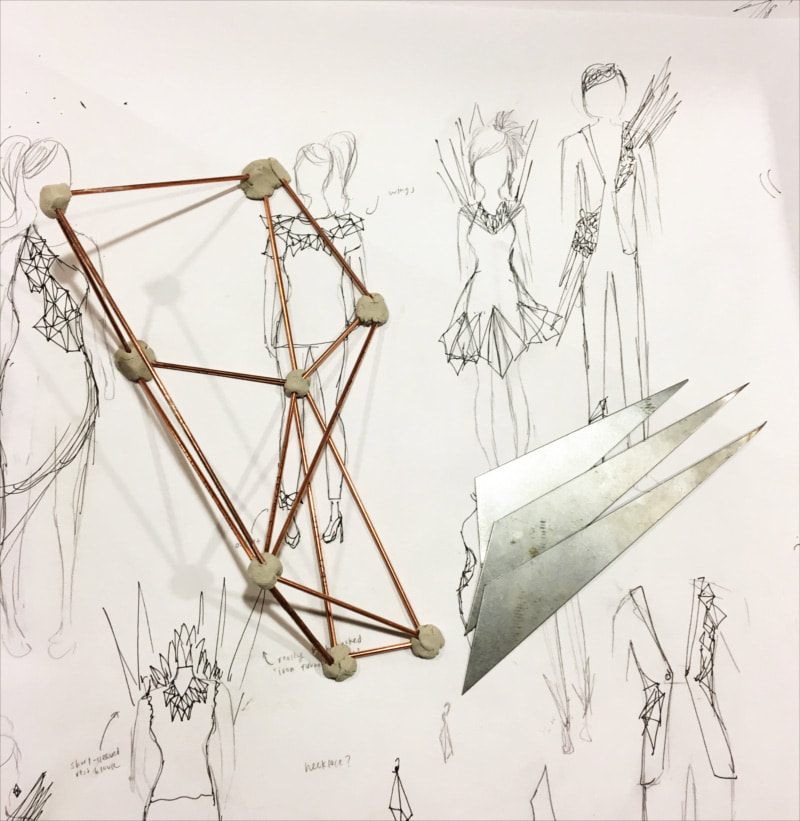

Once we gathered the materials into the MIT Media Lab, which we would be using for our fabrication, we started sketching some initial ideas. I knew I wanted to channel an Amazonian queen as I walked down the runway, with spikes shooting off around my head and from my back. While I love the human-centered design process and designing for clients and users, I appreciated the luxury of designing for myself, because my user was right there and I could ask her as many questions as I wanted, whenever I wanted. Ryan also jumped upon the idea of channeling something badass and incorporating it with haute couture. We spread out a giant sheet of poster paper on a table and I eagerly filled it with sketch after sketch, adding designs as Ryan added suggestions. Pretty early on the sketching cycle, we had hit upon the ideas we wanted. I was very much into the idea of spikes coming off of the shoulders in a neckpiece reminiscent of the Iron Throne from Game of Thrones. Ryan was pro cascading spikes going into and off of the lapel.

|

mitigating risk: using force and load distributions and free-body diagrams |

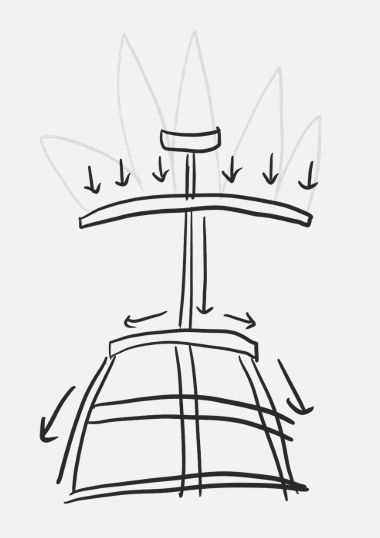

The main problem, and a big safety risk that needed mitigation, was how to incorporate the metal pieces into the garment. Scrap metal is heavy and dangerous, and we needed to find a way to attach the metal pieces that was at once aesthetically pleasing, physically sound, and completely safe. This involved thinking over force and load distributions. Luckily, as both a designer and an engineer, it was easy to make the switch from sketching human body concepts to sketching free body diagrams. For the neckpiece, we settled on a backpiece that spanned my shoulderblades with a spine that ran the length of my back. The piece was attached to me through a collar at my neck and a belt at my waist. The span of the backpiece distributed the weight so that it was not tugging at the collar: a choker is a fabulous accessory until it becomes too true to its name. The attachment at the neck was necessary so that the piece wouldn't buckle; the attachment at the waist was necessary so that the load was distributed.

For Ryan's outfit, we decided on a visible belt this time and a single suspender. The belt allowed for the attachment of the bottom metal plates and the suspender allowed for the support of the top metal plates. |

cardboard aided design |

In order to arrive at our final design, we first made sketches of the designs we wanted and then prototyped using cardboard on top of mannequins. While a dive into the world of CAD could have been a good intermediary, we had only given ourselves a span of a couple of days to start and finish the design, in true make-a-thon fashion, so we wanted a quick and easy way to prototype the design. Thus, our own form of CAD: cardboard, not computer, aided design. We used pins and blue tape to stick the cardboard in place, moving things on the fly as necessary.

|

fabrication |

Once we were satisfied with the prototypes, we began fabrication. To make the metal pieces, we took advantage of the machine shop we had camped out at for the night, using shears, brakes, and presses to cut, bend, and punch the sheet metal. As clamps couldn't quite hold the pieces together in just the right way, we improvised and used magnets to stick the shards on. Then, the two of us began to weld the metal together. To make the garments, we pinned the pieces onto the mannequins and used simple needle and thread to hand-sew the fabric. It was a true partnership: Ryan taught me how to weld, and I taught him how to sew. And like the true mechanical engineer slash fashion designers that we are, we picked nuts and bolts that looked like buttons to fasten the metal pieces together.

The knitted material came to us as white and cream, and we wanted to use black garments, so we needed to dye the fabric black. At first, we wanted to do it in a true machine-shop, hacker style, so we tried to use a recipe we found online to make our own black dye that involved rusted nails and vinegar. We were pretty excited about it, but unfortunately things did not work out. As the time ticked on, we cut our losses and decided that it was all right not to have hand-created the dye. We made do with scrounging up black dye and large enough buckets to dye the fabric en masse (and other creative ways to dye a lot of fabric in little time). |

a stroke of genius & a mishap |

In this process, we had moved from taking up space in the machine shop to taking up space in a lounge in our undergraduate dorm, which happened to be right underneath one of our alcove laundry rooms. Ah, laundry. When you're an engineer, every room becomes a makeshift machine shop in a pinch. You might see washers and dryers. We saw high-velocity mixers and tumblers designed to infuse solids and liquids with efficiency. Which, to two sleep-deprived undergraduates looking for ways to quickly mass-dye a ton of fabric and have them dry enough to immediately sew, seemed a godsend. Don't try this at home; we managed to dye all our fabric (score) and the two machines (not score) black in the process. Our building manager was quite alarmed, but with an hour of us scrubbing, the machines came off spotless, so all was well in the end.

|

results |

Overall, we were quite happy with the final pieces. I modelled a crop top and a skirt that was decorated with shards of bent sheet metal. The outfit was completed by a backpiece that protruded from behind; the shards were spot-welded to each other and then welded onto a shoulder piece that connected to a spine. The spine screwed onto the outfit at two different points, up by the neck with the choker and down by the skirt with the belt. The collar and the belt were lined with the knitted fabric for maximum comfort and each piece was dyed black.

Ryan modelled a jacket made from the knitted fabric and interwoven with shards of sheet metal that stuck out at angles from the left shoulder and the right hip. The shards were spot-welded together, and screwed onto the jacket through a belt and a single suspender strap, both made of sheet metal. I came up with the name for our fashion pieces, Duo Et Machina, as a play on the phrase Deus Ex Machina. Two and the machine seemed an apt way to sum up our process. It was also a bit of an inside joke. The fact that we were able to create two fashion pieces seemingly out of thin air in a span of a couple of days was an accomplishment that seemed to us like deus ex machina. I know that I walked that runway with a lot of confidence but quite little sleep. For reference, my entry to the Trashion Show the year before can be found here in Raccolta.

|